Bill captures in a magical and inspired fictional flourish the flavour of a hellish psychic anguish, revealing his own tender, loving, and creative compassion. It's rare to find stories that make a serious attempt to portray the workings of the mind of a mad person. This may be because of a widespread belief, often promoted by the psychiatric profession, that such a mentality has no logic. But I think that sense, if not of a conventional kind, can be made of these phenomenologies. He creates a story of a miraculous love affair, located within the policical and social context, out of which madness springs, and illuminates the nature of consciousness, the mind and the emotional being.

Bill is an alchemist and a dreamweaver.

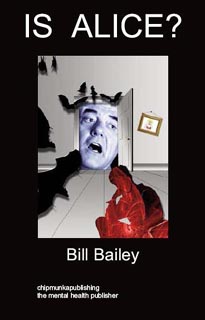

PUBLISHER: CHIPMUNKAPUBLISHING THE MENTAL HEALTH PUBLISHER; COVER BY PAUL JOYCE

D O W N L O A D T H I S E X T R A C T

I S A L I C E ?

B I L L B A I L E Y

FOREWORD

For over a decade I have been the loving partner and carer of a woman diagnosed with “schizo-affective disorder.” Is Alice? incorporates a description of some of her experiences during her last hospitalisation over four years ago within a fictional setting, as Theo struggles to understand Alice’s madness and develop his organic theory of consciousness that might help explain such a devastating illness and the canvas of “normality” from which madness can bloom.

Is Alice? is also a powerful and fictionalised love story. I wrote the novel solely as a manuscript gift for my partner, and publication is therefore dependent upon her wishes. Her primary one, along with pleasure about its surprising publication, is anonymity. She is not “Alice,” and I am not “Theo.” This is not a biography. Fiction is used in Is Alice? to illuminate an actual madness along with a real search for the ideas that may help in understanding the living and political nature of consciousness – the structure of “normality” and the “real” world and its incoherent collapse into the hell that is known as schizophrenia. There are passages from the patient’s point of view, which make this novel an unusual project. That is because the inner landscape of madness does have a logic and meaning that should be acknowledged and evoked, instead of ridiculed or misunderstood. I feel that contemporary psychology – nevermind clinical psychiatry – fails in its attempt to address the nature of consciousness or its creation of the “world.” I believe philosophy underpins psychology, not the other way around.

As my partner’s carer, I have witnessed the depths of her illness and hope my portrayal can help others understand its rhythms of horror. But most of all, I wish to let this novel stand as my tribute to her courage, persistence and love in the quest we have undertaken to put together a world that is cleaner and simpler to know, one that is hopefully closer to the truth. Her life has been transformed as she has reclaimed the territory of her own existence from a life where she felt she deserved nothing and was worth nothing.

I am convinced “schizophrenia” is not a medical problem. It is an existential one. It isn’t a “disease.” It is a catastrophic disordering of the values of the world – a fiction, really, but one that is as “real” as the commonsense world we mistakenly think we know so well. Because it, too, is a fiction we have agreed upon, lies and all. I have called it the social matrix.

My view of the psychiatric treatment of blameless victims of madness is that it struggles blindly to brutally shoehorn a distressing human problem into a medical model that is as primitive as phrenology. In an affront to Hippocrates, psychiatrists can harm their patients. At the very least, simple asylum would do no more harm to human beings who, though mad, still deserve our unremitting respect. Instead there are drugs, electro-convulsive “therapy” and even psycho-surgery – the effects of which are poorly understood by the psychiatric community. Sufferers are incarcerated in prison-like buildings and far too often suffer abuse and neglect by indifferent, badly-trained staff.

Again, though, Is Alice? is a poignant love story that is uncommon and numinous. It was written with love for my partner, and I had no other reader in mind when I wrote it. This changes the accent and meaning of the work. My intention was to please her with a tale woven simply from words. In a sense this returns to the origins of stories themselves. If so, then that pleases me.

CHAPTER ONE

The hush rolled across the Royal Albert Hall like a noiseless wave, when moments before the auditorium was alive with an animal chatter as incessant and relentless – and far less musical – than the canopy of an Amazon rainforest. The house lights were quickly dimming. All eyes refocused on the stage which held a concert grand Steinway piano, a cushioned stool and no other props. The silence of the audience became sepulchral as the seconds slid by slowly. Ten seconds, twenty, then thirty, forty-five, one whole minute. When he finally appeared from behind the stage-left curtains, the breath intake from the audience was sharp, as if from one huge pair of lungs.

Aleksei Cherkasov was a tall man with a lantern jaw. He had once been even taller, but age had rounded his back, bringing his big chin closer to his chest. He was bald, except for a crinkly fringe of still-dark hair that connected the backs of his ears like an Alice band. Having recently celebrated his 81st birthday, Cherkasov walked slowly and carefully across the polished floor of the stage towards the piano. Surely this must be his final public concert. Ten days ago he played the identical programme on the same stage. The over-subscription of that concert led to this extraordinary evening. The legendary Russian maestro demanded that another evening be fixed to accommodate those who failed to get a seat in the first concert. In any other case, this would have been impossible, as the Royal Albert is fully booked over a year in advance. Schedules were frantically shuffled, agents and performers called, all the heavy furniture of bookings were shoved and pushed. Somehow one more evening was created for this astonishing pianist to play again, one last time before he disappeared back into Russia and expected retirement. Aleksei Cherkasov was the last of the great Russian virtuosos of the 20th Century, a man considered the equal of Horowitz and Gilels and even the monumental Richter. If anything, the second bookings were snapped up more rapidly than the first, so Cherkasov insisted some accommodation should be made for those who could bear standing for the length of the whole concert.

In the early years of his fame, Aleksei Cherkasov was treated gingerly by the West. Most of his life was spent as a citizen of the USSR, and he was as outspoken in its support as he occasionally was in criticism of the government. Yet his avuncular charm and ironic wit finally endeared him to people all over the world – that and his absolute command of the piano. In his youth he was known for his fire and ice at the keyboard, but in later years his musicality became more internalised, gorgeously dense and philosophical. His concerts became like séances as he was the medium between this and another world. He completely re-invented the late Beethoven sonatas, and one reviewer exclaimed that he must be experiencing the music exactly as Beethoven would have played it himself. His Debussy was ethereal, like gossamer threads of silk. His Bach unfolded with Euclidian clarity in its celestial geometries. He let it be known that Mozart was his favourite, and developed the composer’s precocious playfulness to bring smiles to the faces of his audiences. Yet he could also tease the depths from shallower works that would have musicians hustling back to have another look at the scores. The respect with which he was held by the musical community was awesome.

Only since the disintegration of the USSR did he begin wearing his Order of Lenin medal when he played. It was not ostentatious. It was a simple statement. Perhaps you could say his citizenship in the USSR fully began with the collapse of his old country. He was contemptuous of the new systems of market-oriented global capitalism and pointed out in interviews that an old three-shell game was being played where the poor became poorer and the rich thrived. In the old days, he commented, everyone at least had a roof over their heads and food in their bellies. Few went without. He didn’t wave the red flag, but he wore his medal whenever he appeared in public. He realised he needn’t say any more than that.

Aleksei Cherkasov sat down carefully on the piano stool and contemplated the white and black keyboard. His chin crushed his splendid black bow tie as he examined for a moment his instruments, those big miner’s hands, now heavily veined and lined. Slowly, he closed his eyes and began to play.

It was Schubert’s B-flat Major Sonata with the extravagantly long first movement based on a melody so sweet that Schubert could not let it go until every drop of emotion could be squeezed from it. It so reminded Cherkasov of a youth that would never be restored. Memories were dim and unreliable. But when he closed his eyes, he imagined he was 13 years old, leaning with his elbows on an old wooden fence, his chin on the back of his folded hands. His huge, serious eyes were following the magical swing of Ludmilla’s petticoats as she walked past his house with two loaves of bread. The longing of the adolescent boy was still in the old pianist’s heart. It was pain, and it was joy. Ludmilla was almost 16, far too old for him, he thought. They weren’t really sexual thoughts. He dreamed only of holding her close to him and burying his face in her blonde ringlets. Just to enfold her, to touch her, that’s all. And that would be heaven. He imagined the two of them lifting from the earth and rising to a palace of stardust where they would lie side by side, listening to the serenade of angels. And for the young Aleksei, Ludmilla was angelic. What magic powers did she possess to lift his whole mind to the heavens? The movement of her body was inexpressibly and exquisitely beautiful…

Cherkasov opened his eyes and followed his fingers on the keyboard. The music took him back to moments like that – so romantic, so youthful, so unblighted by coruscating age. He felt the audience, too, and hoped he and Schubert were helping to illuminate memories of their youthful naivety. He was nervous – as are all performers – but not tense. His focus was to provide access to himself, the deepest meanings of his existence, and thus, he hoped, to Schubert. He raised his eyes from the keyboard, and he was seeing not the stage but those few memories still preserved in the catacombs of self.

Then he did see something else, something peculiar, something completely out of context, as if from another kind of reverie. A man had walked hurriedly onto the stage from the wings. He wore only a pair of underpants and socks. Cherkasov watched as he continued playing. The man stopped downstage in the centre and addressed the audience.

“I desecrate the gods by interrupting this glorious concert, but there is no option,” the man said in a deep, yet steady, bass voice. “I have to tell you a story…”

Cherkasov lifted his hands from the keyboard and placed them in his lap.

“You must hear me. You must let me tell it. It is vital for you, and it is vital for me…”

At this point the amazement of the audience began to turn to disgust and fury. There were shouts from men and women in the darkness of the auditorium.

“For god’s sake, man!”

“Get off!”

“Shut up! Are you crazy!”

The individual voices and words were quickly drowned as many rose from their seats, shouting and protesting at this surreal intrusion. From backstage four men advanced on the man who was now desperately trying to make his voice heard.

Suddenly Cherkasov stood up behind his piano and held up his huge hand. “Nyet. Postoy.

Nye dyeloy eto. Pazhaluysta.”

“Please,” he said slowly in heavily-accented English. “Do not do this. It is a sanctuary. He is a human being. In distress. You were not listening to Schubert. You do not understand.”

The noise from the audience died to a murmur. The four men who now held the intruder all turned to him.

“Who are we to be the judge?” Cherkasov continued, his chin now raised. “This music must have dignity. This man must be treated with dignity.”

He turned and called to the wings. “Dmitri!”

A tall, thin, elegantly dressed elderly man emerged from stage left.

“Provodyi etovo muzhchinu v moyu grimyornuyu i pozobotsya o tom chtobe yemu bilo udobno,” Cherkasov murmured to Dmitri.

The pianist walked slowly over to the partially naked man who was still being held by the stage hands. “I have asked my agent, Dmitri, to take you to my dressing room. After the concert, I will listen to your story.”

One of the stage hands leaned forward and spoke quietly. “Maestro, we have information that this man has escaped from a mental institution. He could be dangerous.”

Cherkasov turned his attention to the man in his underwear. He was perhaps 50 years old, tall, heavily built, with a moustache. “Are you dangerous?”

“Am I resisting these gentlemen?” he replied, adding an ironic smile. “No, I’m neither dangerous nor mad. I’ve been driven to interrupt this celestial music by insane injustice and a world that will not hear me.”

He paused for a moment, his eyes misty. “I hesitated backstage, leaning against the wall with my eyes closed in the darkness. Your playing so moved me, and the B-flat Major is so eternally dear to me, that I almost couldn’t do it. Yet I had to. Maestro, it’s not me. It’s the world. The world is mad…”

Cherkasov flicked his right arm in a gesture of dismissal. “Da. Yes. You’re right. The world. It’s mad.”

“You said this was a sanctuary. That’s what I seek. Sanctuary. Where I can have the time to tell my story.”

“You have found it,” Cherkasov replied softly. “Go now with Dmitri to my room…”

“Please…” the man interrupted.

“Yes?”

“May I just listen from the wings? Just the Schubert, just the one sonata?”

“Of course.” He turned to his agent. “Dima, podai yemu stul i ostansya s nim..”

Cherkasov took the man by the arm and slowly led him to the wings. Dmitri and the four stage hands followed. Then he returned to the piano.

“I will begin again the Schubert,” he murmured to the audience.

o

“We had tickets to your earlier concert here, my partner and I…”

Theo Hawthorn stopped and squeezed his lips together. He was wearing Cherkasov’s dressing gown which was a surprisingly good fit. He was sitting on the small sofa, and the pianist was watching him from the only armchair. Cherkasov had removed his tie and jacket and unbuttoned his shirt, but he was now wearing glasses that made his eyes look owlish. He waited patiently for Hawthorn to continue.

Hawthorn shook his head, as if to clear it. “There was a queue at the box office. A big queue, a huge one, people everywhere. Alice – my partner – had already pre-ordered and paid for the tickets on her credit card, and all we had to do was pick them up. Simple.”

He paused again, but the old pianist remained silent. “You see, Maestro…”

“Don’t call me ‘Maestro.’ It always upsets me. You must call me Alyosha.”

Hawthorn smiled, and his shoulders relaxed a little. “Then call me Theo.”

“Good. Theo. Go on. Tell me.”

He shook his head sadly and looked down at the dressing gown. It was an old one, probably silk, but very worn, black with red piping. “It’s such a complex story. Are you sure you have the time, Alyosha? Or the patience?”

The old man shrugged his shoulders. He didn’t seem tired. “I have some time. Some patience. Enough to listen. I promised.”

Hawthorn blew out a lungful of air and leaned back on the sofa, closing his eyes for a moment. “The Schubert. The B-flat Major. It is very important to Alice and me. When we first met I veered away. She was – is – very beautiful, but she had some fairly severe mental health problems, and I…didn’t feel like I could handle them. At first. Many things happened. I’m trying to accordion the story a little here…”

“Accordion? I…”

“Er, fold it up a little. Make it shorter. But things did happen. Very dramatic things. Between us. At a very crucial moment the Schubert sonata was playing. It was one of my favourites anyway, but at this moment I’m talking about, the heavens seemed to open, and…and there was a different universe.”

Cherkasov nodded his head. His accent was heavy and his words slow. “So you fell in love.”

“Yes, yes…but it was more than that. It changed Alice’s life. It brought hope for her, a chance to escape from regular spells in the hospital that…”

Hawthorn stopped, frustrated at being unable to compress everything into fewer words. “Your performance of that sonata was a key moment…”

Cherkasov waved his hand. “But you. You have these problems too? You are patient? I had to talk to these men. Nurses. From hospital. They wait for you at stage door. They want to take you back to hospital. I told them, shoo, go way, I get back to hospital. I have give my word’.” He shrugged. “I think they still wait for you. Are you lunatic?”

“Me?” Hawthorn gave an ironic smile. “No. Never. No previous problems, no previous admissions. I’ve never even seen a psychologist, never mind a psychiatrist. No history at all of mental illness. I’m a playwright.”

Cherkasov frowned. “You write plays?”

“Not a famous one. I…don’t even make a living. But that’s what I do. The theatre.”

Cherkasov smiled broadly. “Then you are fellow artist.”

Hawthorn chuckled. “Well, that sounds much too grand, compared with what you’ve done.”

The pianist shrugged and tapped his head with a forefinger. “Don’t worry. I know artists. You must have luck. You must be good, but you also must have luck.”

“Ah,” Hawthorn replied. “But with you, it is obvious. No one plays like you. An idiot can see you are a genius.”

Cherkasov laughed out loud and settled back in his armchair, his big chin resting now on the white hairs of his bare chest. “Is not true! Idiots do not know art! How can they tell? Plenty of fine pianists. Which one is good, which one great? Idiots don’t know. Someone tells idiots! This man is good! That is luck! This audience tonight. Someone tell them, this man is a genius! Then I play, and it is genius! No one tell them, they don’t know.” He stopped and scratched his ear. “A few know, maybe. Only few ever know.”

Hawthorn smiled. “I’m with you, Alyosha.” Then he frowned. “Why Alyosha? I thought your name was Aleksei.”

“Alyosha is diminutive.”

“Oh. That must be a honour. Thank you.”

“I hate too much forms.”

“Formality?”

“Da. Formality. My English was better, but now I’m old. I love languages. Almost as I love music. I speak also Mandarin…”

“Chinese?”

“Japanese, so…interesting, that language. German. Italian, so beautiful, and Spanish, also. And French…so Debussy. Language is like piano. You need practice. In London I get practice one last time.”

“Maybe not the last time,” Hawthorn grinned. “You’ll always have a packed house here.”

Cherkasov heaved himself out of the armchair. “I am not civilised. You want drink? Somebody gave me good Scotch whisky. What is called? A malt.”

“Please. Don’t bother.”

“Glasses? Ah. Good.” he said as he looked laboriously in a cabinet beside the dressing table. He picked two glasses, placed them on top of the dresser, then reached behind a huge vase of flowers to retrieve a bottle of whisky. He poured two drinks, moved back to his chair and held out the large one to Hawthorn.

“I cannot drink like before. Too old. A little wine, a taste of whisky, maybe vodka. What is bad is good for you.” He chuckled to himself as he settled slowly back into the armchair.

“Thank you very much,” Hawthorn said before taking a sip of the whisky. “And thank you most of all for listening to me. Not having me thrown out. I was desperate. Couldn’t think of any other way to do it. No one would listen. At the hospital, they think I’m mad, won’t let me out. This afternoon I noticed they forgot to lock the door to the emergency exit, the stairs. I don’t have my keys, I have no money. I walked to the Albert Hall from North London in my socks. In the newspaper I saw you were giving another concert, and all I could think of was talking to the audience – and you – telling you of the injustice. I suppose that was mad. Yes, that’s mad. But I’m not mad. Yet now they have proof I’m mad. A world of paradox.”

“Yes!” the old pianist gestured with the hand that held the whisky. “The world is paradox. Not what it seems.”

Hawthorn stared at Cherkasov. “You were so kind. You stopped playing, stopped them from taking me away. I owe you...”

Cherkasov interrupted. “Tell me. How old?”

“How old am I? Fifty-six.”

“Ah. Still a young man. Age tells you nothing is important. Too late. So much wasted on unimportance…”

Hawthorn studied the old man as he waited for him to continue. His eyes were set on the wall behind the sofa, and his chin was again resting on his chest. His bald head was sprinkled with liver spots, and the hand holding the whisky glass shook a little as he moved it slowly to his mouth Then, in a sudden movement, he threw his head back and drained the glass.

“Much time wasted on illusion,” he continued as he slowly lowered his arm with the empty glass to his lap. “I’m old now, so more time to listen. You have something to say. So I listen. You listen to my music, now I listen to yours. People – some – are as music. Words are melody, but there is more, much else. Harmony. Dissonance. Percussion, resolution…”

“The fugal rhythms of self,” Hawthorn muttered.

“What’s that? A fugue. Yes. Like a fugue. OK, return to theme. You are standing in a queue outside here for first concert. With your wife.”

Hawthorn took a deep breath and leaned his head back on the sofa. He could feel the muscles in his foot twitching from the side-effects of the drugs he had been given by force. He suspected that was why it was so difficult to follow one thought with another.

“Alice and I are not married. I call her my partner. At the ticket window, there was no one inside. It was just a machine. It spoke mechanically, but in a bright woman’s voice. ‘Please insert your card.’ Then, ‘Please lean forward and look directly into the red square with your right eye’.”

“Ahhhh,” Cherkasov growled angrily and rose again from his chair. “I would refuse! I tell you, I would refuse even if God himself descended from heaven and appeared at Albert Hall. More whisky?”

Hawthorn shook his head, raising his glass to show how much he had left.

“These days you telephone,” the old pianist continued, “you talk to machine. You want money? Machine. Pay money? Machine. Ask a question? Machine. Soon maybe the machines raise children so the parents can work, work, work. I tell you, Theo, I’m glad I’m old. I don’t want to live in such a world. Once we walked to shops, bought something, had a conversation with the owner, even a drink, maybe knew his family. Today? Order from the computer, pay with cards.”

Hawthorn sighed and nodded. “Every day it becomes more difficult, and there are more problems. Alice didn’t pass the iris scan…”

Cherkasov wrinkled his face, rounding his lips. “What is this?”

“You put your eye to a hole next to the machine, and your iris – the coloured part of your eye – is compared with a photograph they have on…some computer. If they don’t match, the transaction is refused. It’s never happened before with us. Technology, Alyosha. Instead of clerks at the bank, they have machines. Much cheaper. And they work all day every day, don’t get sick and don’t have holidays. Just upgrade the software every now and then. I was surprised when I found one at the Royal Albert. Here, at least, there is something of tradition, I thought. But, no. The ticket office is now a machine. With an iris scan. I suppose that was why the queue was so long. No one cares how long a queue is, how long people have to wait, whether it’s raining or cold. Before, it took maybe four people behind a counter to issue the tickets. One machine replaces all these people – and of course makes no mistakes! It was Alice’s card. Alice has loads of money in the bank, no problem. But the machine says the iris does not match. Something is wrong with the machine, but you can do nothing…”

“This is disgusting,” Cherkasov muttered. “Russia is becoming this way also. You should see the rich now. Like jackals. As always, eating the flesh of the poor. Fattening themselves with food they do not need, wanting only more. My country has…traded justice for greed. So very sad.”

Hawthorn turned for a moment, thoughtfully, facing the dressing-room door. He took a sip of whisky, then lowered the glass slowly. “Any other evening, any other concert, we would have simply left the box office. Walked away. Gone home. But this night was different. Alice booked the tickets months ago, the day we first saw the advertisement. Aleksei Cherkasov plays the Schubert B-flat Major sonata. For many years we had listened only to the recording. It was a special evening. We looked forward to it, we planned, talked about it, laughed, hugged each other…”

Hawthorn turned back to the pianist, pressed his lips together and leaned forward, elbows on knees, holding the whisky glass in his left hand. He stared at the shiny toes of Cherkasov’s black concert shoes. “Alice turned towards me. Her eyes were helpless, and there were tears. What could she do? What could we do? On such an important evening. For us. People behind us in the queue were getting restive, told us to move. I asked them to be patient and told Alice to wait at the machine while I went to find a human being. The doorman. I tried to explain things, he just kept shaking is head. So, I…I took my clothes off.”

Cherkasov cocked his head comically. “You took off clothes?”

“Yes!”

The old pianist started laughing slowly and softly, rocking back and forth in his chair. He took off his glasses and squeezed his nose with thumb and forefinger, his eyes closed. Then he exploded, threw his head right back and laughed from his belly.

“Ha!” he said finally. “You took off clothes! Down to skin!”

“Yes! It was all I could think to do. By this time people in the queue were really grumbling, looking at their watches, complaining to us. When I took my clothes off, there was shouting, shoving. Chaos was breaking out. The doorman was dumbstruck. He didn’t know what to do.

“I said, ‘Let us in, and I’ll put my pants back on. We have paid. We have bought tickets. Your machine is broken.’ You understand?”

The old pianist was nodding his head, still laughing. Hawthorn couldn’t help himself, as he felt his lips crease into a smile, then a short laugh.

“It’s the first time I’ve seen the humour in it…” he said finally. His expression changed as he continued. “But the doorman was on his mobile phone. He was calling the police. So. My last gambit. Failed. I put my underpants back on. Like now. Same underpants. And I looked for Alice, had trouble finding her. She was standing, her back against the wall. A man was in front of her, shouting abuse. I looked at her eyes…and knew…immediately. I shoved the man away, pushed him. He turned on me, but I ignored him. Because I knew…from her eyes. Alice. The eyes are seeing…some other story of the world, all within.”

Hawthorn stopped as his voice trailed off. His head was lowered as he stared at the carpet between his feet.

Cherkasov noticed for the first time the playwright was balding on the crown of his head. “Your partner…”

“My partner is mad. First time in…many years, can’t remember. When she goes, it is immediate. One moment she’s OK, the next she’s gone. There’s no reaching her, no penetrating her world. I grabbed her in my arms, just in my underpants. I held her and cried. But she was struggling. She doesn’t like to be touched when…when she’s in that world. She believes it is a horrible joke, that I despise her, that I have to hold her because it is my fate, and she wants to release me from…this fate. Oh, it’s so difficult, Alyosha. I can’t explain it. Everything in time and space twists suddenly, and all the demons clatter from hellish holes and set upon her soul with sharp teeth and bloody knives. Despite her struggles, I still held her close to me. I knew it could be weeks – or even months – before I saw my beautiful Alice again.”

Hawthorn sat up suddenly and finished the whisky with a single swallow. Carefully he placed the empty glass on the arm of the sofa. “Anyway, the police came, and they phoned the…the mental health swat team, whatever they’re called. A psychiatrist arrived. By this time the concert must have already begun. We were outside the Royal Albert, standing in the cold. Alice was…was… They took us both to a hospital in north London. I was so angry. I was talking to the psychiatrist at the hospital, they were questioning me, Alice had been taken to another room. Then they sectioned me. Sectioned both of us.”

“Section? What is section?”

“It is a power held by the State to imprison those who are judged to be insane – against their will. By force, if necessary. It has been a nightmare beyond my powers to describe it. I had witnessed it before, when Alice was ill years ago, but only as an outsider. You have no rights, you are no longer believed, anything you say. You are not a person. You are on a different island, one you have not seen before. You are pinned down and given powerful drugs, whether you need them or not. If you want to know the meaning of hell, just enter an institution where you become a dumb, meaningless animal.”

There was a long pause as Cherkasov replaced his glasses and studied his visitor. Neither man moved as the silence slowly became more profound.

“It is a difficult problem,” the old pianist said finally. “In three days I return to Moscow, and this moment I am now very, very tired. I hope you understand. But this I will promise you. You must leave the name of this hospital and the name of someone I can speak to. Tomorrow I will call…no, I will come. Dmitri!”

Almost immediately the dressing-room door opened, and the long, lugubrious, worried face of the agent appeared. Cherkasov held up his hand and turned to Hawthorn.

“Give these details on a paper to Dmitri, and I will ask for him to call for you a taxi…”

Hawthorn shook his head. “No, I think they’ll be waiting for me downstairs, Alyosha. I’ll go with them.”

He stood up and started to take off the dressing gown.

“No, no, no,” Cherkasov said. “You take this with you. Go in dignity. It is mine for many years, but now I give it to you.”

Almost reluctantly Hawthorn re-tied the belt to the old dressing gown. “I don’t know how to express my gratitude. Your kindness…in the circumstances…is beyond belief. I so much loved your performance tonight. If only…”

With some difficulty Cherkasov stood up and held out his hand. “You do this for me, and you must promise. OK? You do this. You write to me. In Russia. Dmitri will give you my address. Tell me all you have to tell me. I will be your friend. I have some influence, a little. Not so much as people think, but a little. And tomorrow I will come. I will talk to them. You must be released from this place. I will see to it. That is all I can do for you.”

Hawthorn held onto his hand and looked into his eyes. For the first time in nearly two weeks he felt something very heavy crawl off his back. Perhaps there was, he thought, a little hope.